In steels, even trace additions of chromium or nickel can alter crystalline structures. They can shift transformations from ferrite-pearlite to martensite or bainite. Carbon is the driver of hardness. Yet, such extra elements in alloy steels refine grains, tempering response, and corrosion resistance. In this article on alloy steel vs. carbon steel, we’ll explore how these compositional tweaks create differences in mechanical and metallurgical behavior.

Carbon Steel and Its Types

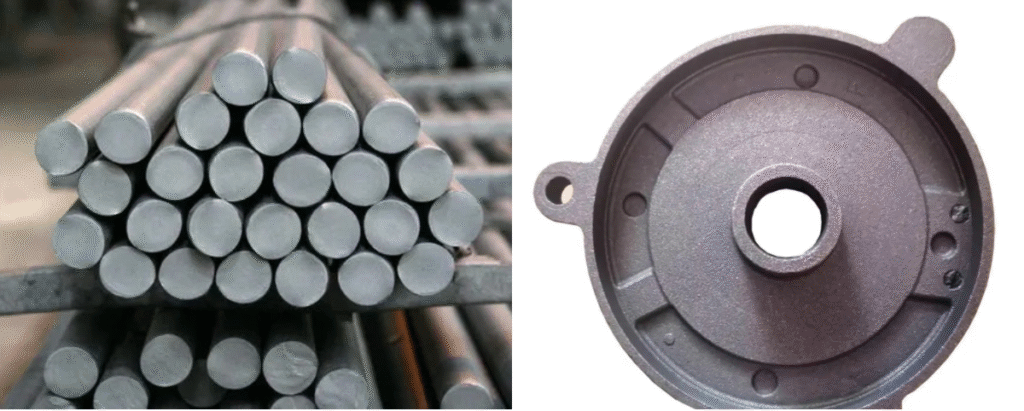

Carbon steel is iron with controlled amounts of carbon. Its properties change with shifts in carbon content. That makes carbon steel multipurpose in demanding engineering environments.

- Low Carbon Steel: Such type contains up to 0.25% carbon. Its microstructure is mostly ferrite with small pearlite regions. It’s very ductile and weldable. You might see it in automotive body panels and structural sheets. That’s where high formability matters.

- Medium Carbon Steel: Carbon content is 0.25-0.60%. It can be heat-treated for tempered martensite or bainite. It fits crankshafts, forgings, and high-load machine parts.

- High Carbon Steel: It has around 0.60-1.00% carbon. When quenched, it can accomplish hardness and wear resistance. The microstructure might have martensite or tempered martensite. It’s a go-to choice for cutting tools, dies, and high-stress springs.

- Ultra-High Carbon Steel: Such grades can reach up to 2.0% carbon. They form hard martensite but can turn brittle if not wisely tempered. Heat treatment keeps microcracks at bay. They’re used for knives, punches, and other precision tools for high hardness.

Alloy Steel and Its Types

Alloy steel differs from carbon steel in terms of chosen alloying elements. At the atomic level, it prompts specialized microstructures. It assures strength, toughness, and corrosion resistance.

- Low-Alloy Steels: They contain 1% to 5% of Cr, Mo, or Ni. Many pressure vessels utilize such grades for creep resistance at high temperatures. They might experience quenching and tempering to refine grain structure and fatigue performance.

- High-Alloy Steels: They surpass 5% total alloy content. Many of such grades employ preeminent chromium levels to tolerate chemical or thermal attacks. Examples include high-chromium tool steels that preserve their hardness near 500°C.

- Stainless Steels: At least 10.5% chromium is in their passive oxidation-resistant layer. The FCC structure of austenitic 304 suits cryogenic applications. Ferritic and martensitic variants use different heat treatments for magnetic properties and hardness.

- Tool Steels: They use tungsten, chromium, vanadium, and molybdenum for wear resistance. For instance, H13 survives thermal shock in die-casting molds. Heat treatment forms hard carbides that keep edge retention under abrasive conditions.

- Microalloyed Steels: They use minute amounts of niobium, titanium, or vanadium for grain refinement. Even a few hundred parts per million Nb can raise yield strength. Such steels skip heat treatments and use controlled rolling and cooling for high toughness.

- Maraging Steels: They are nickel-based steels with ultra-low carbon content. Aging produces intermetallic precipitates that increase strength. Maraging steels are ductile and are preferred in aerospace applications for rocket motor cases.

Alloy Steel vs. Carbon Steel: Key Differences

Composition and Alloying Elements

When experts debate alloy steel vs. carbon steel, they focus on how extra elements impact performance. Carbon steel has up to 2.0% carbon with limited manganese or silicon. On the other hand, alloy steel may include chromium, nickel, molybdenum, and vanadium in unique amounts. Small additions of such elements can shift the ferrite-pearlite balance for particular traits. Chromium above 5% can improve wear resistance. Nickel in the 3-5% range boosts toughness at low temperatures. Molybdenum in concentrations of 0.2-0.5% lowers creep in high-temperature environments. So, it defines the real essence of alloy steel vs. carbon steel.

Microstructure and Phase Transformations

In alloy steel vs. carbon steel discussions, professionals emphasize how each metal’s microstructure responds to thermal cycles. Carbon steel transitions between ferrite, pearlite, bainite, or martensite are according to carbon content and cooling rate. With alloy steels, chromium or nickel stabilize certain phases. It can delay or accelerate transformations during quenching. Carbides may form in high-chromium or high-vanadium steels for uniform hardness distributions. Nickel-rich steels can keep a stable austenitic phase at room temperature to impact final toughness. Meanwhile, small additions of boron can change hardenability profiles. Henceforth, it renders alloy steel vs. carbon steel choices dependent on mechanical goals.

Heat Treatment and Hardening Mechanisms

Heat treatment differs when comparing alloy steel vs. carbon steel. Carbon steel uses simple normalizing, quenching, or tempering to control pearlite and martensite formation. Yet, alloy steels can respond differently due to interactions among alloying elements. Chromium and molybdenum can intensify resistance to softening during tempering for a secondary hardening peak. Vanadium and niobium might precipitate fine carbides during tempering for wear resistance. Controlled atmosphere furnace treatments are key to carbon control in high-alloy steels. Vacuum heat treatment can also adjust surface specs and decarburization. It shows why alloy steel vs. carbon steel heat treatments need metallurgical expertise.

Mechanical Properties in Extreme Conditions

The difference is notable when evaluating alloy steel vs. carbon steel under exciting loads, temperature, or corrosion. Carbon steels may show predictable strength at room temperature. Still, alloy steels are used in high-heat turbine components. Chromium and molybdenum additions help resist creep at high temperatures. Nickel-enriched steels can retain toughness well below freezing for cryogenic storage tanks. Slight chromium (above 2%) can improve passivation layers in corrosive settings. 0.5-1% copper can protect steel in marine conditions. It illustrates how alloy design beats plain carbon steel when failure cannot be risked.

Welding and Fabrication Considerations

Welding experts compare alloy steel vs. carbon steel to comprehend crack susceptibility and heat-affected zone performance. Higher carbon content in plain carbon steels can trigger hardened zones near the weld if cooling is too fast. Alloy steels with higher hardenability might face hydrogen-induced cracking if not preheated or post-heat treated. Alloying boron can demand welding consumables to match strength and toughness. Temper-bead welding procedures help control microstructure in steels with high sulfur or phosphorus. Filler metal selection helps uphold the desired mechanical properties when dissimilar joints are required. Remember, skilled welding processes optimize alloy steel vs. carbon steel joints.

Applications and Future Directions

In real, the choice between alloy steel vs. carbon steel counts on the environment and mechanical demands. Pressure vessels, crankshafts, and aerospace gears use chrome-moly or nickel-steels for their strength and ductility. Axles and structural beams may use carbon steel cost-effectively. Still, they utilize fine-grain practice for toughness. Future modernizations microalloy with titanium or niobium for stable carbonitride precipitates for fatigue life. Powder metallurgy methods develop alloy steel vs. carbon steel with a uniform distribution of alloying elements. Thus, it confirms that refined chemistries and heat treatments will expand steel performance.

If you have queries regarding choosing between alloy steel vs. carbon steel, contact us.